Blog Post 2 – The gendered prosthesis – exploring the expression and affect of gender through disability and sex

The following blog post will explore the gendered dimensions of disability and the gendered aspects of rehabilitation with of prostheses (prosthetic limbs, knitted breasts). I will also explore how our relationship with male condoms as sexual prostheses during intercourse shape our attitude towards intimacy.

Bodies are defined and articulated in relation to the context they are in (Jain 1990) to the extent that bodies both occupy and are occupied by, the environment. Such an interaction with the day-to-day environment is precisely what Marx would argue enables concepts and ideas to become tangible, relatable and lived; the physical evidence of our humanity. Of relevance to this material approach is the process of corporeally ‘accepting’ a prosthetic limb and learning to walk. According to this framework of understanding, the prosthesis can be theorised as the material means with which one physically and spatially re-instates themselves in the world.

The prosthesis is commonly theorised according to the extent to which an amputee can fully ‘restore’ their body. Jain (1999) argues that the artificial limb is a discursive framework and social agent in its own right that can be used to explore broader questions about the ‘disabled’ body in an otherwise ‘able-bodied’ world. Beyond a phenomenological theorisation of the body in the world exists an emerging realm of inquiry seeking to understanding how and where disability is situated within the body, and who exactly the prosthesis is designed to satisfy. Rehabilitation requires an interrogation of positionally – who is being targeted, effected or involved in the process of prostheticisation? Is the arduous process of rehabilitation endured to medicate ‘ableist’ narratives and the Western medical gaze? or is it to fulfil the desires of the user? Arguably, the two are indecipherable. What are the gendered, religious, ethnic, financial, political and material repercussions of this?

Booher (2010) explores the gendered consequences of rehabilitation, looking specifically to womens’ experience adapting to a prosthetic limb. Specifically, she describes the way in which the prostheticised female body is represented as superficially ‘docile’ on popular media platforms as the epitome of social governance and control. Celebrities with prostheses are venerated as ‘supercrips’ – those who, despite their loss of limb or disability, achieve unprecedented triumphs. Whilst some may argue that the depiction of ‘supercrips’ in mainstream media marks an effort to ‘normalise’ the disabled body in the public eye, Booher refutes this arguing that, instead of celebrating difference, such depictions of supercrips in fact celebrate the merits of disabled bodies that successfully imitate a ‘normal’ body, thereby reinforcing the binary between able and disabled. Such a notion is broadly explored through the Foucauldian idea (1977) that the body is separable from the ‘social body’ and alienated within a pedagogy and thereby comparable to the unachievable, yet ever so desirable standard of a ‘normal’ functioning body. Therefore, supercrips are seemingly remarkable in the public eye because they are ‘broken’ bodies with the potential to perform at the level of the ‘complete’ body (Booher 2010, 75) and have, therefore, complied as the society intended. Furthermore, the expectations imposed on prosthetic bodies as discussed above, demonstrates the convergence between concepts of the ‘normative body’ and gender. Despite the initial disorientation of loosing a limb, amputees are expected to aspire to rehabilitate themselves to the standard of the normative able-body we are all so familiar with. This is what Scheper-Hughes (1987) might describe as womens’ bodies being monitored and surveilled by Western medical and technological conventions of the ‘the body politic’ that collectively strive to mask difference and cosmetically blur the line between the end of an amputee’s stump and the beginning of the artifice.

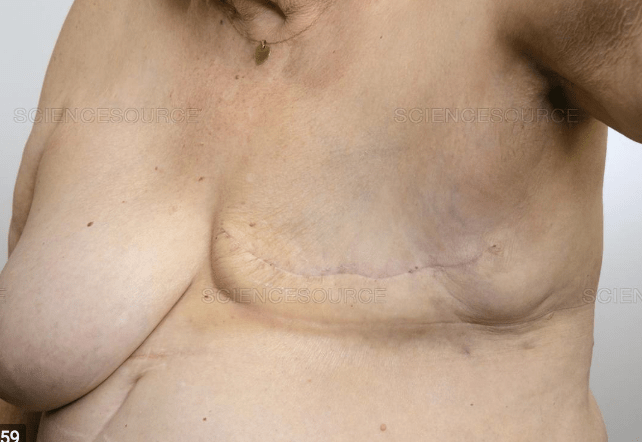

‘Knitted Knockers’

Watch this video below to find out more about ‘Knitted Knockers’ – a nationwide US non-profit organisation.

This group of volunteers gather together to knit prosthetic breasts for women who are suffering breast cancer or have recently recovered from a mastectomy. Unlike silicon breast prostheses that are expensive and uncomfortable, these knitted breasts are designed to prioritise comfort, affordability and practicality as they are light-weight, soft and only $2 per breast. The company ‘Knitted Knockers’ provides free instructions to anyone looking to volunteer and video tutorials which are available on YouTube. The women behind this initiative sought to bring a renewed sense of confidence to women suffering from, or recovering from breast cancer – many of whom also experience hair loss and reduced self-esteem.

These knitted breast prosthetics, specifically designed for women are officially adopted and recommended by over 1,491 medical clinics across the US. Of March 2020, an estimated 181,462 knitted prostheses have been provided by volunteers of the organisation.

‘Knitted Knockers’ was started by founder, Barbara Demorest who survived breast cancer in 2011 following a mastectomy. Though she was eager to return to work appearing ‘normal’ after her surgery, Barbara was advised not to disturb the repairing scars on her chest with a silicon breast prosthesis. As a consequence of her own personal encounter with breast cancer, Barbara developed the idea of knitting a ‘stuffable’ prosthetic alternative. That teams of volunteers across the US are working together to produce personalised gendered prostheses for cancer-survivors demonstrates an act of solidarity pursued to provide women with the means to reclaim defining outward markers of their femininity. By wearing these knitted prosthetic breasts, women can reclaim a state of normalcy in their lives and locate themselves alongside other women.

Another study by Koçan & Gürsoy (2016) focused on how a mastectomy can impact on the body image of female cancer survivors. Through semi-structured interviews with 20 participants, the results found 4 reoccurring themes including: the meaning of the breast, patient experience with mastectomy, body image changes and sociality. Most women in the study reported that breasts indexed femininity, attractiveness and being a mother, many went so far as to say that without their breasts they felt incomplete in both their bodies and in their sexual relationships with others. These findings are also supported by Davies et al., (2017) who discovered that a mastectomy can cause long-term emotional strain in the lives of patients that is not taken seriously by health care providers. Overall, Koçan & Gürsoy (2016) discovered the potential damage to identity, body image and self-esteem that many women face post-mastectomy, not to mention the real impact of loosing ones breast on mental health. One participant explained her experience seeing her scars in the mirror for the first time after the operation:

“I didn’t want to see the operation area at all; I saw it when I was back home. Before seeing it, I knew that I was going to feel the emptiness but when I saw it, I felt very different (crying), words are never enough to explain”

There has been a growing interest in the phenomenology of the amputated body over recent decades, particularly with respect to prosthetic rehabilitation. Kurzman (2001) argues that language, as a means to explain or describe the sensation of rehabilitation with a prosthesis cannot sufficiently articulate the highly personal nature of what if feels like to learn to move a prosthesis on one’s body. Kurzman refers to the specificity and incommunicability of the proprioceptive experience of manipulating a limb in space and the steps taken over time to accepting it as a part of one’s body. Kurzman (2001) nods towards the real struggles endured by amputees trying to accommodate their newly reformed bodies post-amputation, including the arduous and unnatural sensation of re-learning to walk albiet half-way through their adult lives. Therefore, Kurzman demands that amputation is a process that conjures a closer observation of body gestures and the manner in which one walks and holds themselves in space.

So, how do such adaptive processes extend to phenomenological encounters with other types of prostheses?

Eric Greene (2013) offers a ‘phenomenology of condoms’ closely observed through the brand name ‘Durex’ – a title proposing that condoms are the tough, ‘machine-like’ counter-part to our biological bodies. The man wearing the condom is implied as ‘man-as-machine’ – an ideology facilitating a state of sexual durability and pathological invincibility in the face of infection. ‘Durex’ is therefore advertised as a brand of condom to suit one’s apparently ‘superhuman’ erection. The suffix ‘-ex’ of Durex implies something distinctly robust.

With reference to the act of sex itself, Greene (2013) proposes that condoms behave as a tangible, noticeable division separating your own body from the other person to the extent that wearing one during intercourse feels awkward and, through its presence and physicality, actually reminds us of the dangers of copulation, arguably making the sex less ‘sexy’ because of the underlying sense of guilt and fear.

The presence and utility of condoms as an interruption to sex acts as a reminder of a the potential consequences of intimacy – the pause between foreplay and penetration dedicated to adorning the contraceptive, leaving room for contemplation, momentary reflection and the impending dissolution of arousal. Upon initial encounter, its clear that condoms are engineered to imitate the feeling of sex as the latex sheath is lubricated to accompany the expectations surrounding the condition of the vaginal orifice.

Deadroff (2013) investigated the sexual values and ‘condom negotiation strategies’ shared by Latino youths living in the United States. The study arrived in response to reports that young Latino men and women aged between 16-22 across the US are more at risk of contracting STIs, but are less likely to use condoms. 694 participants within that age range took part in this study and 61% were female. Deadroff (2013) uncovered that Latino’s increased exposure to STIs presents as a consequence of cultural values surrounding sexual intercourse and the gendered etiquette of sex itself. Fundamentally, participants stated that traditional cultural norms do not tolerate casual conversation about sex, even between two partners and especially not from women. Furthermore, female participants in the study articulated the importance of prioritising male sexual pleasure and deeply respected pre-marital virginity. The outcome of this research was to demonstrate why sexual health initiatives seeking to navigate issues of sexually-transmitted infections should begin by observing the condom negotiation strategies and cultural values of Latinos surrounding the performativity and gendered aspects of sex.

Another study by Crosby et al (2013) explored the gender differences related to condom perception and use. It is suggested that American men use condoms during approximately 25%, and women only 22%. Data was collated using a survey sent out through mailing list to 65,859 male and female participants over the age of 18, Crosby et al (2013) discovered that the primary excuse for not using condoms during sex was because condoms didn’t fit or were uncomfortable. More specifically, ill-fitting condoms caused reduced sensation or decreased pleasure, therefore making the sex itself feel ‘unnatural’ or even uncomfortable.

Overall, by understanding the phenomenology of condoms as prostheses, it is possible to observe the various ways in which people have in response to, and around condoms as artificial implements so critical, not merely in terms of controlling the population and the spread of sexually transmitted infections, but in the physical, social and cultural act of sex itself. What does it mean to use a condom, or perhaps, more crucially, what does it mean to not use a condom? How is barrier contraception not simply an individual decision but a collective choice? Beyond the prevention of pregnancy, how do condoms as material intersections in our sexual lives influence how we approach sexual intercourse? What are the gendered implications of using condoms and where should we (0r can we) successfully locate condoms in accordance with cultural, religious and social values attached to sexual relationships.

Bibliography

Booher, A. K. (2010, September). Docile bodies, supercrips, and the plays of prosthetics. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 3(2), 63-89.

Crosby, R. A., Milhausen, R. R., Mark, K.P., Yarber, W. L ., Sanders, S. A., & Graham, C. A. (2013). Understanding Problems with Condom Fit and Feel: An Important Opportunity for Improving Clinic-Based Safer Sex Programs. New York: Springer.

Davies, C., Brockopp, D., Moe, K., Wheeler, P., & Abner, J. (2017). Exploring the Lived Experience of Women Immediately Following Mastectomy: A Phenomenological Study. Cancer Nursing, 40(5), 261-368.

Deadroff, J., Tschann, J. M., & Flores, E. (2013, December). Latino Youths’ Sexual Values and Condom Negotiation Strategies. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 45 (4), 182-190.

Foucault, Michel 1977 Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Alan Sheridan, trans. New York: Random House.

Greene, E. (2013, July). The Phenomenology of Condoms. 13(2), 113.

Jain, S. S. (1999). The Prosthetic Imagination: Enabling and Disabling the Prosthesis Trope. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 31-54.

Koçan, S., & Gürsoy, A. (2016, October). Body Image of Women with Breast Cancer After Mastectomy: A Qualitative Research. J Breast Health, 12(4), 145-150.

Scheper-Hughes, N., & Lock, M. M. (1987, March). The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1(1), 6-41.

Blog Post 3 – Masks, Pollution and Violence

Amidst the current COVID-19 pandemic, how have facial masks as protective prosthetics entered mainstream media and altered our attitude to others? This blog will explore the intersection between concepts of pollution, ‘matter out of place’ and xenophobia.

According to Goffman (1995), the human face is the gateway to communication with others. Social encounters demand what he refers to as ‘face work’ in the sense that our facial expressions are consistently responding to and seeking to satisfy queues from others. In this way, ‘face-work’ is a sensitive and measured process that mediates our relationships with others. Goffman demands that face-work is a deeply rooted and ‘embodied process’ that is outwardly performed by the face and employs the work of spoken language through the mouth.

In recognition of this reflection on the face, Talley (2014) argues that cosmetic facial surgery is a process with converging material and symbolic elements. The decision to aesthetically alter the presentation of one’s face is enforced, not merely by the individual, but by what Schemer-Hughes describes as the ‘body politic’ – the integrated cultural ideologies promoted through the tacit execution of social maintenance that governs the body. Culturally determined notions of beauty, symmetry and normality become a part of the collective conscious and understanding of what is appropriate about the human face. According to beauty narratives, seemingly ‘abornmal’ or ‘irregular’ aspects of one’s face can be corrected by undergoing facial surgeries. The process of facial surgery itself involves various actors – the surgeon, the patient, assisting medical staff – and takes place within a site-specific surgical environment that transforms the human body into the medical subject upon entering the clinic. One’s face undergoes a series of material processes executed with the view of solving the pre-existing anxieties it once created. The collaborative efforts of all actors involved in the surgery contribute towards an outcome that is constituted according to collective notions of what is and what is not attractive in a face. Furthermore, during the surgery, the patient loses autonomy over the appearance of their face that becomes temporarily at the mercy of the surgical team, entrusted with a mutual understanding of what the patient’s face should look like. This investment of trust in the cosmetic surgeon to whom the patient surrenders their face for alteration demonstrates a need for validation from others that their face is normal.

With the emergence of Covid-19, facial masks have become increasingly popular around the world as a method to protect against the air-bourn virus.

Facial masks have a strong association with respiration, infection and disease as they form a physical barrier between ones mouth and contamination from the outside world. A study observing the effectiveness of face masks to protect against air pollution in Beijing, China was conducted by Cherrie et al., (2018), inspired by the increase in use of disposable face masks in the capital city. The study involved testing the filtration efficiency of 9 different masks (available on the market to consumers) on four volunteers. Volunteers adorned the masks and were subsequently exposed to diesel exhaust particulate pollution. The efficiency of the masks was measured according to the concentration of black carbon residual on the masks. The results demonstrated that the average black carbon residual found on masks ranged between 0.26% and 29%, and the average ‘leakage’ of polluting matter ranged between 3%-68%. Cherrie et al (2018) concluded that masks on market to the general public are not a fully effective means of protection against pollution. One of the major reasons for this was due to them being loose-fitting and uniform in size, leading to increased chance of polluting matter leaking through the mask.

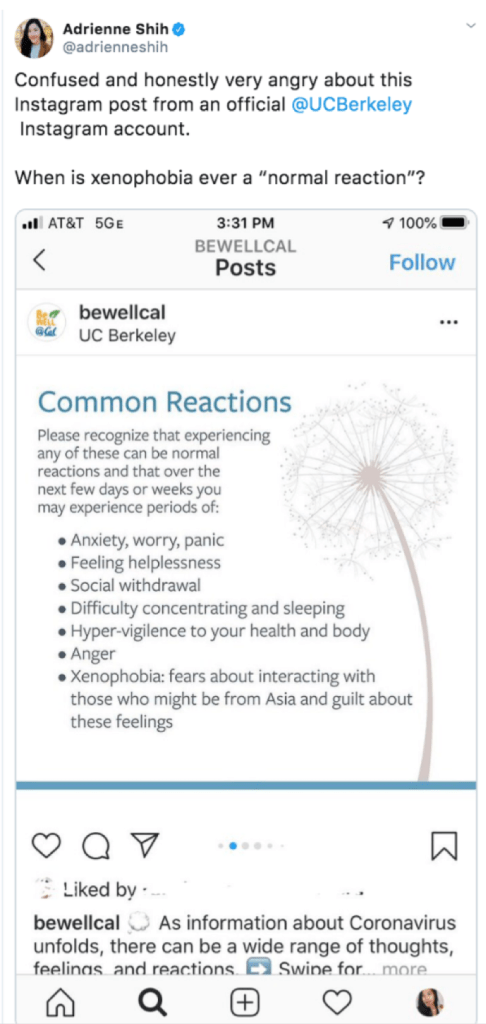

Despite this, Chen (2012) observes that, in Western contexts, the surgical mask has emerged as a material index of globalisation and disability for its potent relationship with notions of security and infection. Specifically, such masks have developed a complicated reputation not merely as visible signifiers of protection from negative substances and a reminder of polluting forces, but a physical barrier preventing the most natural face-to-face interactions between the self and others. Therefore, the face, ‘as a prioritised site of human engagement’ (Chen 2012) becomes denigrated and jeopardised. Paradoxically, surgical are symbolic of alternative prostheses that contribute to the physical and biological body as a polluting agent, rather than someone avoiding pollution.This conjures a more frightening matter concerning the way in which such masks, imbued with cultural significance, causing a rise in intolerant and unforgiving racial mis-representations or stereotypes. According to Maddox (2006), racist assumptions and stereotypes are born out categorising tendencies that strive to put people into boxes according to their phenotypic features, therebyencouraging a shift in behaviour and attitude as a result. In a recent article concerning the way in which damaging stereotypes and racial abuse in response to coronavirus – also nicknamed ‘COVID-19’ – reports the increasing instance of verbal violence and racism amongst children and adults stereotyping people of Asian descent accused of ‘carrying the virus’ from Wuhan, China.

Covert forms of racism are visible in the sense that fear has shaped how people behave, or more accurately do not behave, in public – avoiding public areas where one might come into contact with polluting agents. Medical Anthropologist, Monica Schoch-Spana (2020) states that those who occupy a ‘different national, ethnic or religious background have historically been accused of spreading germs’.

This Tweet posted by UC Berkley caused a significant level of distress by their attempt to normalise xenophobia:

Accordingly, it is possible to observe the way in which Chinese nationals have become selectively been demonised for wearing protective surgical masks. Such prostheses have become so strongly associated with disease that they have developed a logic somehow overriding their purpose as tools created precisely with a view to preventing illness and to be used by self-aware, and socially conscious individuals.

Another way to conceive of masks in the way their materiality as barriers and how they consequent face-to-face social interactions. Masks as prostheses are sensitive markers of one’s disability because they are highly visible because they cover the face – the mediator of language and expression – and therefore attract the curiosity of others and disrupt social interaction (Chen 2012). The disturbance arises as a consequences of violation of the social contract – that in order to be an active and included member of society, one must bare their face visible to others, a prosthetic tool intended as a medical preventative, masks are counterintuitively perceived as ‘disabling’ because they force onlookers to think about illness and contamination, thus instilling a sense of fear.

Bibliography

Chen, M. (2012). Masked States and the “Screen” Between Security and Disability. Women’s Studies Quarterly,, 40, 76-96.

Cherrie, J. W., Apsley, A., Cowie, H., Steinle, S., Mueller, W., Lin, C., Loh, M. (2018). Effectiveness of face masks used to protect Beijing residents against particulate air pollution. BMJ, 446-452.

Goffman, E. (1995, November 8). On Face-Work An Analysis of Ritual Elements in Social Interaction. Psychiatry, 18(3), 213-231.

Maddox, K. B. (2006, April). Rethinking Racial Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination.

Scheper-Hughes, N., & Lock, M. M. (1987, March). The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1(1), 6-41.

Talley, H. L. (2014). Facial Work: Aesthetic Surgery as Lifesaving Work. In H. L. Talley, Saving Face: Disfigurement and the Politics of Appearance (pp. 24-46). NYU Press.

Blog Post 4 – Teeth and dentures – overcoming nature’s fascinating designs / Cochlear implants and ‘parent-as-mediator’.

Dentures are dental prostheses are designed to re-establish lost biological mechanisms of the teeth (chewing, crunching or tearing food) that are reduced because they are no longer present. For this reason, dentures are more commonly associated with older demographics who have lost their teeth with age. The design and engineering behind dentures must mimic the oral capacities that humans have evolved over time, including the elaborate process of omnivorous mastication whereby the upper and lower jaw interconnect and align in relation to the rest of the skull to enable the mechanical break-down of food in the mouth (Koussoulakou & Margaritis, 2009). Often dentures are never quite as effective as biological teeth and though such prostheses have been repeatedly manufactured and revised over time, their design is yet to adequately replaced by normal teeth. The evolution of human dentition has also shaped, and been shaped by, our ability to speak and create vocalised sounds, including the capacity for language.

Prostheses are not simply artificial replacements or passive additions to the body, they are ‘extra-somatic’ extremities that articulate the confrontation between the personal body and technology and transform the way we sensorially engage with our surroundings. Ansar (2016) demonstrates that prostheses of the body have simultaneously bridged the gap and been the gap between ‘human and nonhuman, abled and disabled’, mortal and superhuman, and precisely for this reason, prostheses exist as materials that disturb the relationship between technology, the body and ideology. As such, prostheses are socio-technical objects with the capacity to eclipse the very limits of what the body can do. That is, prosthesis, in whatever form (ie. dentures, limbs, cochlear implants) shape the identity, physical capacity, language, food consumption, audition, and psychology of users.

Furthermore, in the case of dentures, these oral prostheses are markedly unique in the sense that their relationship with the body is made vulnerable as a result of their fundamental incompatibility. Contemporary oseointegrated dentures are made from titanium as a material that the body does not naturally reject and can therefore be screwed directly into oral tissue, thereby avoiding embarassing accidents like this happening:

Laura Mauldin (2014) explores paediatric cochlear implantation (CI) and the clinical encounter as two processes that co-contribute to the meaning of ‘deafness’. A CI typically manifests as a surgically integrated silicon device implanted behind the ear and composed of various electrodes that channel through the ear canal and into the cochlea, the area of the inner ear responsible for the conversion of sound waves that entering the ear into electrical signals to be redirected to the auditory cortex. Cochlea implants do not ‘cure’ deafness, but they stimulate the cochlea which enable the user to detect environmental sounds.

Mauldin (2014) specifically argues that Cis are material objects that shape our understanding of deafness and those who are deaf. The CI is often discussed as a tool that the user must learn to accommodate and use, thereby offloading a significant amount of responsibility onto the user who must ‘train the brain’ to hear with the device. An inability to do so translates swiftly, albeit unjustly, into one’s inability to train their own brain. This paradox of moral ownership is unique in the case of neonates. Children recognised as deaf are labelled as such from an early age, and from this moment of a diagnosis, are subjected to particular handling and treatment within society – their learning processes are affected as a result of their lack of audition. In her book, Mauldin continues to explore the medicalisation of deafness, stating that the silence surrounding deafness and the lack of attention paid towards the deaf community is the result of cultural pressures to communicate via spoken word. The medicalisation of deafness in children is generally approached with the ultimate goal of getting them to speak out loud aided by cochlear implant prostheses, consequently suppressing the idea that sign-language could ever be a primary option, or the most appropriate option for deaf children. Indeed, this hegemony contributes to health policy changes and the nature of rehabilitation. However, as a parent of a deaf child, Mauldin (2016) also unearths an important perspective on how rooted cultural prejudices towards spoken communication problematise and complicate the role of the parents and the family dynamic.

The western contemporary attitude towards deafness is contextually situated in a current climate in which the body is understood to be constantly coming into being. CIs are therefore developed and advertised in such a way that capitalizes on the plasticity of the brain, particularly in children. Mauldin argues that during the patient-practitioner interaction, the mother often assumes the responsibility of the mediator – between her child and the doctor.

Consequently, Mauldin highlights the gendered orientation of the clinical encounter as the mother is challenged with assuming the moral high ground and making healthcare choices on behalf of her child. Supporting this notion, Ginsburg and Rapp (2001) explore how the family is the most important social centre in which the concept of disability is established and can be re-articulated. Furthermore, the way in which CIs generate meaning is dependent on the relationship between mother and child and how the parent encourages the child to deal with their deafness.

Hearing impairment is one of the most common disabilities as approximately 466 million adults and children around the world are expected to be diagnosed with impaired hearing – having a hearing capacity of 40dB or less in adults, and 30dB or less in children (WHO, 2020). A study conducted in Shiraz, Iran by Mostafavi et al (2017) investigated the obstacles faced by parents of young hearing-impaired children learning to use a cochlear implant, with a view to improving family-based interventions.

16 mothers and fathers with hearing-impaired children (diagnosis confirmed within 12 months) between the ages of two and seven took part in this phenomenological study. All completed in-depth interviews related to their child’s ability.

Recurring themes from the interviews were condensed into five main ‘clusters’, including: a need for access to health care, psychological needs, emotional needs in children, rehabilitation needs and money-related needs. All of the clusters discussed in interviews can be specialised into domains of support. Expressed worries about ‘access to healthcare’ included general concerns surrounding a lack of facilities or implants available to them. Concerns for psychological support included discussion around reduced self-esteem, anxiety, resiliency, stress levels and pessimism. These concerns also extended to emotional concerns for the child including behavioural issues or disturbed sleep cycles. Many parents reported a general lack of information or understanding about deafness and explained feeling largely unequipped to deal with hearing-related issues faced by their children. Finally, all parents discussed financial fears related to the unaffordable costs of clinical services or treatment, rehabilitation or supplementary support. Many parents discussed having to apply for financial loans and associated feelings of helplessness.

Overall, Mostafavi et al (2017) concluded that guardians of children with rehabilitating with cochlear implants feel disadvantaged. Overall, an inability to access disability services for structural or financial reasons places excessive emotional and psychological strain on families. Furthermore, parents felt a significant sense of guilt and concern surrounding their child’s disability because, if they felt they could not provide their child with access to services and treatment while young, they would consequently be responsible for their child’s ability to thrive in society later on in life. Evidently, Mostafavi et al (2017) revealed how mothers and fathers of hearing-impaired children become the mediators between their children and healthcare providers, shedding light on the socio-economic and psycho-social repercussions of this. Parent’s not only felt financially helpless in terms of gaining access to treatment or rehabilitation (many of which reported affordances such as selling their cars, houses or taking out money loans) but feared a personal inability to sustain their child’s quality of education or support them emotionally and empathetically.

Bibliography

Koussoulakou, D. S., & Margaritis, L. H. (2009). A Curriculum Vitae of Teeth: Evolution, Generation, Regeneration. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 5(3), 226-243.

Mauldin, L. (2013, December 13). Precarious Plasticity: Neuropolitics, Cochlear Implants, and the Redefinition of Deafness. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 39(1), 130-153.

Mauldin, L. (2016). Introduction: Medicalization, Deaf Children, and Cochlear Implants. In L. Mauldin, Made to Hear: Cochlear Implants and Raising Deaf Children (pp. 1-26). University of Minnesota Press.

Mostafavi, F., Hazavehei, S. M., Oryadi-Zanjani, M. M., Rad, G. S., Rezainanzahed, A., & Ravanyar, L. (2017, September 25). Phenomenological needs assessment of parents of children with cochlear implants. Electron Physician, 9(9), 5339-5348.

WHO. (2020, March 1). Deafness and hearing loss. Retrieved from World Health Organisation: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss