According to Goffman (1995), the human face is the gateway to communication with others. Social encounters demand what he refers to as ‘face work’ in the sense that our facial expressions are consistently responding to and seeking to satisfy queues from others. In this way, ‘face-work’ is a sensitive and measured process that mediates our relationships with others. Goffman demands that face-work is a deeply rooted and ‘embodied process’ that is outwardly performed by the face and employs the work of spoken language through the mouth.

In recognition of this reflection on the face, Talley (2014) argues that cosmetic facial surgery is a process with converging material and symbolic elements. The decision to aesthetically alter the presentation of one’s face is enforced, not merely by the individual, but by what Schemer-Hughes describes as the ‘body politic’ – the integrated cultural ideologies promoted through the tacit execution of social maintenance that governs the body. Culturally determined notions of beauty, symmetry and normality become a part of the collective conscious and understanding of what is appropriate about the human face. According to beauty narratives, seemingly ‘abornmal’ or ‘irregular’ aspects of one’s face can be corrected by undergoing facial surgeries. The process of facial surgery itself involves various actors – the surgeon, the patient, assisting medical staff – and takes place within a site-specific surgical environment that transforms the human body into the medical subject upon entering the clinic. One’s face undergoes a series of material processes executed with the view of solving the pre-existing anxieties it once created. The collaborative efforts of all actors involved in the surgery contribute towards an outcome that is constituted according to collective notions of what is and what is not attractive in a face. Furthermore, during the surgery, the patient loses autonomy over the appearance of their face that becomes temporarily at the mercy of the surgical team, entrusted with a mutual understanding of what the patient’s face should look like. This investment of trust in the cosmetic surgeon to whom the patient surrenders their face for alteration demonstrates a need for validation from others that their face is normal.

With the emergence of Covid-19, facial masks have become increasingly popular around the world as a method to protect against the air-bourn virus.

Facial masks have a strong association with respiration, infection and disease as they form a physical barrier between ones mouth and contamination from the outside world. A study observing the effectiveness of face masks to protect against air pollution in Beijing, China was conducted by Cherrie et al., (2018), inspired by the increase in use of disposable face masks in the capital city. The study involved testing the filtration efficiency of 9 different masks (available on the market to consumers) on four volunteers. Volunteers adorned the masks and were subsequently exposed to diesel exhaust particulate pollution. The efficiency of the masks was measured according to the concentration of black carbon residual on the masks. The results demonstrated that the average black carbon residual found on masks ranged between 0.26% and 29%, and the average ‘leakage’ of polluting matter ranged between 3%-68%. Cherrie et al (2018) concluded that masks on market to the general public are not a fully effective means of protection against pollution. One of the major reasons for this was due to them being loose-fitting and uniform in size, leading to increased chance of polluting matter leaking through the mask.

Despite this, Chen (2012) observes that, in Western contexts, the surgical mask has emerged as a material index of globalisation and disability for its potent relationship with notions of security and infection. Specifically, such masks have developed a complicated reputation not merely as visible signifiers of protection from negative substances and a reminder of polluting forces, but a physical barrier preventing the most natural face-to-face interactions between the self and others. Therefore, the face, ‘as a prioritised site of human engagement’ (Chen 2012) becomes denigrated and jeopardised. Paradoxically, surgical are symbolic of alternative prostheses that contribute to the physical and biological body as a polluting agent, rather than someone avoiding pollution.This conjures a more frightening matter concerning the way in which such masks, imbued with cultural significance, causing a rise in intolerant and unforgiving racial mis-representations or stereotypes. According to Maddox (2006), racist assumptions and stereotypes are born out categorising tendencies that strive to put people into boxes according to their phenotypic features, thereby encouraging a shift in behaviour and attitude as a result. In a recent article concerning the way in which damaging stereotypes and racial abuse in response to coronavirus – also nicknamed ‘COVID-19’ – reports the increasing instance of verbal violence and racism amongst children and adults stereotyping people of Asian descent accused of ‘carrying the virus’ from Wuhan, China.

Covert forms of racism are visible in the sense that fear has shaped how people behave, or more accurately do not behave, in public – avoiding public areas where one might come into contact with polluting agents. Medical Anthropologist, Monica Schoch-Spana (2020) states that those who occupy a ‘different national, ethnic or religious background have historically been accused of spreading germs’.

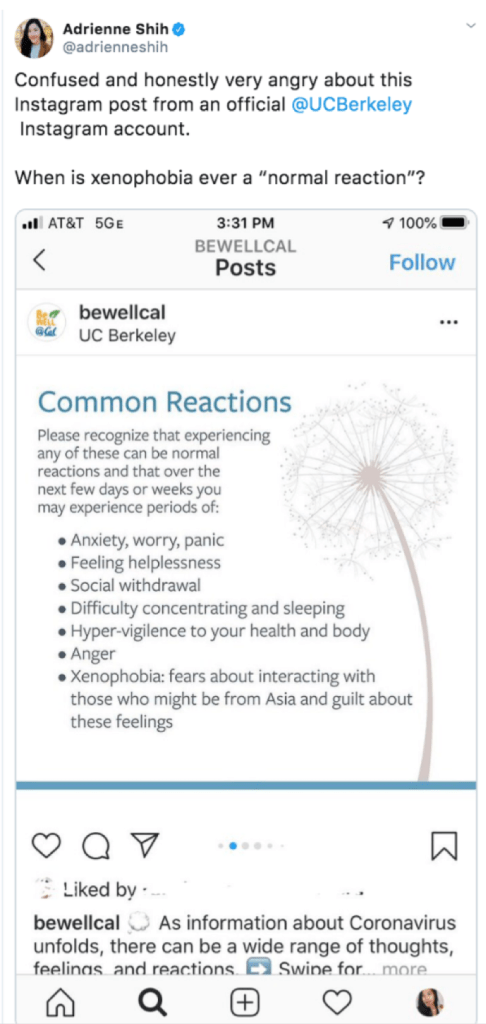

This Tweet posted by UC Berkley caused a significant level of distress by their attempt to normalise xenophobia:

Accordingly, it is possible to observe the way in which Chinese nationals have become selectively been demonised for wearing protective surgical masks. Such prostheses have become so strongly associated with disease that they have developed a logic somehow overriding their purpose as tools created precisely with a view to preventing illness and to be used by self-aware, and socially conscious individuals.

Another way to conceive of masks in the way their materiality as barriers and how they consequent face-to-face social interactions. Masks as prostheses are sensitive markers of one’s disability because they are highly visible because they cover the face – the mediator of language and expression – and therefore attract the curiosity of others and disrupt social interaction (Chen 2012). The disturbance arises as a consequences of violation of the social contract – that in order to be an active and included member of society, one must bare their face visible to others, a prosthetic tool intended as a medical preventative, masks are counterintuitively perceived as ‘disabling’ because they force onlookers to think about illness and contamination, thus instilling a sense of fear.

Bibliography

Chen, M. (2012). Masked States and the “Screen” Between Security and Disability. Women’s Studies Quarterly,, 40, 76-96.

Cherrie, J. W., Apsley, A., Cowie, H., Steinle, S., Mueller, W., Lin, C., Loh, M. (2018). Effectiveness of face masks used to protect Beijing residents against particulate air pollution. BMJ, 446-452.

Goffman, E. (1995, November 8). On Face-Work An Analysis of Ritual Elements in Social Interaction. Psychiatry, 18(3), 213-231.

Maddox, K. B. (2006, April). Rethinking Racial Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination.

Scheper-Hughes, N., & Lock, M. M. (1987, March). The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1(1), 6-41.

Talley, H. L. (2014). Facial Work: Aesthetic Surgery as Lifesaving Work. In H. L. Talley, Saving Face: Disfigurement and the Politics of Appearance (pp. 24-46). NYU Press.